Finding Curve Inflection Points in PostGIS

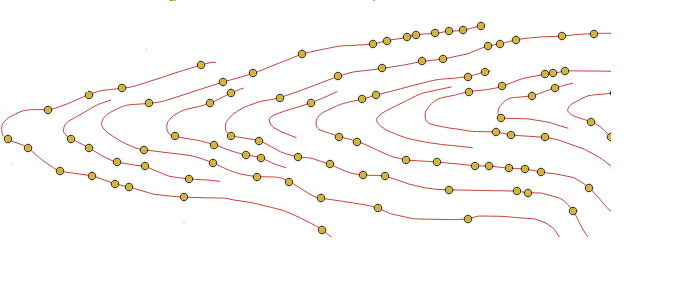

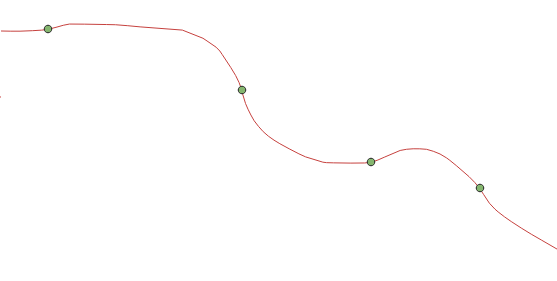

Posted on February 6, 2022In this blog post I will present a way to find inflection points in a curve. An easy way to understand this: imagine the curve is the road we are driving along, we want to find the points in which we stop turning right and start turning left or vice versa, as shown below:

We will show a sketch of the solution and a practial implementation with PostGIS.

A sketch of the solution

This problem can be solved with pretty standard 2d computational geometry resources. In particular, the use of the cross product as a way to detect if a point lies left or right of a given straight line will be useful here. The following pseudo-code is based on the determinant formula:

function isLeft(Point a, Point b, Point c){

return ((b.X - a.X)*(c.Y - a.Y) - (b.Y - a.Y)*(c.X - a.X)) > 0;

}In general, I am against implementing your own computational geometry code: the direct translation of mathematical formulas are often plagued with rounding-off errors, corner cases and blatant inefficiencies. You would be better off using one of the excellent computational geometry libraries such as: GEOS, which started as a port of the JTS, or CGAL. Chances are that you are using them anyway, since they lie at the bottom of many GIS software stacks. This holds true for any non-trivial mathematics (linear algebra, optimization…). Remember: floats are NOT real numbers

In this case, where I cared a lot more about practicality than sheer efficiency, the use of SQLs numeric types, which offer arbitrary precision arithmetics at the expense of speed, prevents some of the rounding-off errors we would get with double precision, sparing us to implement fast robust predicates ourselves.

PostGIS implementaton

I have long felt that Postgres/PostGIS is the nicest workbench for geospatial analysis (prove me wrong). In many use cases, being able to perform the analysis directly where your data is stored is unbeatable. Having to write a SQL script may be a throwback for some users, but works charms in terms of reproducibility and traceability for your data workflows.

In this particular case we will assume our input is a table with LineString geometry features, each one with its unique identifier. Of course, geometries are properly indexed and tested for validity before any calculation. It is also often useful during development to limit the calculation to a subset of the data through an area of interest in order to shorten the iteration process for testing results and parameters.

The sketch of the solution is:

- Simplify the geometries to avoid noise (false positives).

ST_SimplifyorST_SimplifyPreserveTopologywill suffice. - Explode the points, keeping track of the original geometries, this can be easily done with

generate_seriesandST_DumpPoints. - We need 3 points to calculate

isLeft: 2 to define the segment and the point to test for. So, for each point along theLineString, we get the X,Y coordinates of the point itself and the 2 previous points. We will be checking for the current point position in relation to the segment defined by the two previous points. This also means that the turning point, when detected, will be last point of the segment, that is: the previous point. I found this calculation to be surprisingly easy through Posgres window functions. - Use the above points to calculate a measure for isLeft.

- Select the points where this measure changes.

As usual, good code practices in general also apply to the database. In particular, CTEs can be used to clarify queries in the same way you would name variables or functions in whatever programming language: to enable reuse, but also to enhance readability by giving descriptive names. There is no excuse for any of the eye-burning SQL queries that are too often considered normal in the language.

Look at the sketch solution and contrast with the following implementation to see what I mean:

WITH

-- Optional: area of interest.

aoi AS (

SELECT ST_SetSRID(

ST_MakeBox2D(

ST_Point(467399,4671999),

ST_Point(470200,4674000))

,25831)

AS geom

),

-- Simplify geometries to avoid excessive noise. Tolerance is empiric and depends on application

simplified AS (

SELECT oid as contour_id, ST_Simplify(input_contours.geom, 0.2) AS geom

FROM input_contours, aoi

WHERE input_contours.geom && aoi.geom

),

-- Explode points generating index and keeping track of original curve

points AS (

SELECT contour_id,

generate_series(1, st_numpoints(geom)) AS npoint,

(ST_DumpPoints(geom)).geom AS geom

FROM simplified

),

-- Get the numeric values for X an Y of the current point

coords AS (

SELECT *, st_x(geom)::numeric AS cx, st_y(geom)::numeric AS cy

FROM points

ORDER BY contour_id, npoint

),

-- Add the values of the 2 previous points inside the same linestring

-- LAG and PARTITION BY do all the work here.

segments AS (

SELECT *,

LAG(geom, 1) over (PARTITION BY contour_id) AS prev_geom,

LAG(cx::numeric, 2) over (PARTITION BY contour_id) AS ax,

LAG(cy::numeric, 2) over (PARTITION BY contour_id) AS ay,

LAG(cx::numeric, 1) over (PARTITION BY contour_id) AS bx,

LAG(cy::numeric, 1) over (PARTITION BY contour_id) AS by

FROM coords

ORDER BY contour_id, npoint

),

det AS (

SELECT *,

(((bx-ax)*(cy-ay)) - ((by-ay)*(cx-ax))) AS det -- cross product in 2d

FROM segments

),

-- Uses the SIGN multipliaction as a proxy for XOR (change in convexity)

convexity AS (

SELECT *,

SIGN(det) * SIGN(lag(det, 1) OVER (PARTITION BY contour_id)) AS change

FROM det

)

SELECT contour_id, npoint, prev_geom AS geom

FROM convexity

WHERE change = -1

ORDER BY contour_id, npointHere’s what the results look like for a sample area: