Cloud Optimized Vector

Posted on April 22, 2022A few days ago a coworker of mine sent me a recent article by Paul Ramsey (of Postgis et al. fame) reflecting on what would a Cloud Optimized Vector format look like. His shocking proposal was … (didn’t see that coming)… shapefiles!

I understand the article was written as a provocation for thought and as such makes some really good points. I also think that the general discussion over what a “cloud optimized vector” format would look like can be productive, but I am afraid that some less experienced developers (or, God forbid, managers!) would take the proposal of pushing shapefiles as the next cloud format a bit too literally, so I thought I would give some context and counterpoint to that article.

Him being Paul Ramsey and me being… well… me, I’d better motivate my opinion, so here comes a longish post. I will try to analyze what makes something cloud optimized based on the COG experience, see how that could be applied to a vector format, then justify why shapefiles should be (once again) avoided and finally see if we can get any closer to an ideal cloud vector format.

What makes something cloud optimized anyway?

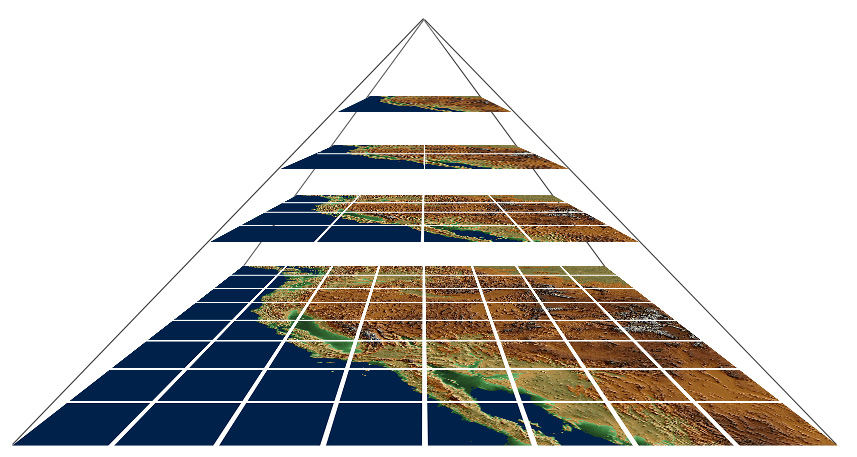

Cloud Optimized GeoTiffs are technically just a name for a GeoTiff with a particular internal organization (the sequencing of the bytes on disk). Tiff is a old format (old as in venerable) that allows for huge flexibility in terms of internal storage, data types, etc… For example, an image can be stored on disk one line after the other or, as is the case with COG, in small square “mini images” called tiles. Those tiles are then arranged in a larger grid and then several coarser-resolution layers (called overviews) of such grids can be stacked together to form an image pyramid.

Of course, all data is properly indexed within the file so that accessing a tile of any pyramid level is easy (seeking byte ranges and at most some trivial multiplications or additions).

Whenever data is fetched in chunks through a channel with some latency (be it disk transfer or network), the efficiency of the overall processing can be improved by organizing data in the same order it will be read by the algorithm to compensate for the cost of setting up each read operation (seek times of spinning disks or protocol overhead in network communications).

A corollary of this is being that data formats are not efficient per se, in the void: it will always depend on the process/algorithm/use case. For example, for a raster point operation (such as applying a threshold mask for some value), organizing data line by line with no overviews is more efficient than a COG would be (…and that is why the Geotiff spec allows for different configurations).

When dealing with spatial data, that principle gets hit by a loose version of Tobler’s First Law: data representing an area nearby is more likely to be accessed next. For example, when a user is viewing an image, tiles that are close to the ones on screen are more likely to be fetched next than tiles representing remote areas (because users pan, do not jump randomly).

So what is the use case COG is having in mind? Well, in case you hadn’t figured it out already, it is mainly visualization1. Overviews allow for zooming in and out efficiently and tiles help with moving along a subset of the higher resolution.

This pattern has been the ABC of raster optimization for decades in the geospatial world. Be it tile caches, tiling schemes, WMS map servers, etc… they all2 try to have the same properties:

- Efficient navigation along contiguous resolutions (through overviews, pyramids, wavelets).

- Efficient access of contiguous areas at a given resolution (tiling).

This also turns out to be a pretty sensible organization if you cannot know in advance what kind of processing will be performed, because it gives you fast access to a manageble piece of the data: be it a summary (overview) or a subset (a slice of tiles) or a combination of both.

Notice what it does not allow, though: it leaves you in the dry if you need a subset based on the content of the data: eg. I would like to see all pixels with a red channel value of 42: in that case you would have to read the whole image.

COG is just a name for a GeoTiff implementing that organization. It goes a bit further than that by forcing a particular order3 of the inner sections, which is smart because a client can ask for a chunk at the beginning and it will take all the directores (think indices, metadata) and probably some overviews, which makes sense, because most viewers will start with the lowest zoom that covers the bounding box. It is also a nice organization for streaming tiles of data.

With that in mind, what would it mean for a vector format to be “cloud ready”? Well it sure should allow for the visualization use case, and here it would mean loosely speaking “rendering a map”, so that gives us an idea:

- Having the ability to navigate different zoom levels / scales / generalization(s).

- Efficient rendering of nearby areas at a given resolutions.

Notice that point 1 as a process is much harder in vector than in raster formats: for rasters it is (mostly) a question of choosing what “summary” measure we pick for the overview pixel corresponding to the underlying level (nearest neighbor, interpolation, average, other…). Generalizing a vector is much harder, first because it can break topology and geometry validity in many ways, but also because deciding if/how to represent different features at different scales requires for cartographic design knowledge. But that is not relevant for the format itself, it just needs to be flexible enough to allow for different geometries at different resolutions and be efficient in navigating the different resolutions (we do not care how hard it was to generate the different resolution levels).

While I think these two requirements are the equivalent of what a COG offers for raster, I am unsure we would consider that enough in the vector case. For example, we might not consider acceptable not being able to have subsets or summaries based on attribute values, so there is a whole new level of complexity for vector at the format level as well. It all boils down if by vector we mean features or just geometries.

Now that I’ve established the two conditions I think define cloud optimization, at least by COG standards, let’s first dive into why I would say Shapefiles are not the future of the cloud.

The noble art of bashing shapefiles

A lot has been argued over the years on the problems with shapefiles. I will just refer here the problems specifically relevant in a cloud setting.

First, they are a multiple file format. There is a cost in the OS layer for opening a file (name resolution, checking permissions), and the web server will probably add another layer on top of that, so please let’s not choose a format for the cloud that means opening a .shp, .dbf, .prj, .dbx, .qix… and potentially all of these.

It’s limited to 2GB of file size. Most COGs are effectively BigTiffs, and easily need to go far beyond that. In any case, one of the reasons for moving to the cloud is being able to process larger data.

As for the use cases, they’re not even good for representation: you need several of them, one for each layer/geometry, to make most general maps (except maybe choropleths and other thematic maps). That already means multiplying the number of files even more.

Secondly, Paul’s article seems to care about property number 2: accessing contiguous areas at a given resolution. That is not cloud ready in the same way COGs are. We also need multi-scale map representation (property 1). You can of course use some sort of attribute to filter which elements should appear at different resolution levels, but that means attribute indexing and clashes with spatial ordering. The other option would be using different shapefiles for different layers so, even more files.

The tool for spatial ordering the article suggests would certainly be useful for a streaming algorithm where spatial contiguity is relevant, but then again there are options tailored for this use case.

Is there a better option?

For the representation use case which is what COGS provide, there certainly is, and has been around for a long time. It’s just that we call them vector tiles.

Vector tiles are exactly the application of the old tiling schema idea to vectors. It’s just that instead of mini-images, we have a pbf encoding of an format for encoding geometries and attributes.

Those tiles are then organized into a the same organization of grids and pyramids for different resolutions that we had in a COG. It’s just that most of the times, the tiling is not dependent of the dataset (though it can be), but globally fixed, with a set of well-known tile schemas.

The tiles can have different schemas and information at different resolution levels (zoom) to allow for different generalization and visualization options.

We can pack all those tiles into a single .mbtiles file, which is a sqlite-based format containing the tiles as a blob. Having a global tile scheme is nice because you can then use sqlite’s .attach command to merge datasets, for example. And you can include any metadata (projection, etc…) inside a single file.

And of course there are libraries for rendering them in the browser (that is their primary use case), among many other things. But Paul already knows that, since PostGis itself can generate them.

Are we there yet?

Well, for representation, at least we are close… but what if we want more complex queries over that (think spatial SQL)? With an .mbtiles alone you would need to actually decode each .pbf and query the attributes, so no luck there…

In a sqlite-based format (like .mbtiles or GeoPackage), it should be possible to add extra tables for queries that may or may not reference to the main tiles… but that’s an idea yet to be developed…

The other caveat for vector tiles is the possible loss of information as a general geometry repository. Internal VT coordinates are integers (mainly because they are optimal for screen rendering algorithms), so that means there is a discrete resolution for each zoom level. Special care has to be taken into account so that there is no loss of information (ie. making sure the zoom levels are enough for the internal raster cell to be below the resolution of the measuring instruments). So again, they may not be suitable for every application.

Conclusion

I hope I made my point on why I do not think shapefiles are the future of the cloud based vector formats (I wrote this in a bit of a hurry) and, more importantly, that the “cloud optimization” concept of the raster world can only be applied to the vector formats in a limited way. I do think there is an interesting space to explore, though… Of course I may be completely wrong and maybe Peter has actually found something.

Time will tell, I guess…

The trick is that some cloud processing platforms such as the Google Earth Engine are in fact processing on a visualization driven also called lazy processing scheme: only the data that is visualized at any moment by the user gets processed, on demand, so the same principle applies.↩︎

Actually, not all, there are more sophisticated methods like wavelet transforms allowing for multi-resolution decoding in formats like .ECW/MrSID (commercial) or JP2000, but for the purpose of this post let’s just call it a very sophisitcated pyramid.↩︎

For many applications, the hard requirements are tiles and overviews. The order of IFDs may not have much of an impact. I encourage the user to try and read a “regular” tiled tiff through

/vsicurl/in QGIS. Or even a raster geopackage, for that matter.↩︎